Welcome to IE Law School

IE Law School is widely recognized for our rigor in global legal education. With a wide range of academic programs, research endeavors and unique projects, we prime professionals to take the lead in pursuing Justice and the Rule of Law across international borders and societies.

The inspiration of our core values and our rich teaching methodologies help students to build multiple competences that transcend traditional academic and professional frontiers at the service of an internationally-minded and impactful spirit; in the hands of our faculty of researchers and practitioners and a global network of leading organizations, companies, and firms, you will build a professional career on the global stage that leads to positive change.

The Next Fifty: Shaping the Future of Global Legal Practice with Soledad Atienza

SETTING STANDARDS FOR ACADEMIC RIGOR AND INTERNATIONAL PRESTIGE

At IE Law School, we are committed to your professional and personal growth through innovative programs and impactful research endeavors to foster your purpose: making a significant contribution to the principles underpinning Justice and the Rule of Law. You will hone your global outlook and build upon the solid foundation set by the five key principles of IE University: technological immersion and innovation; an entrepreneurial mindset; diversity; a focus on the humanities and sustainability.

UNLOCK YOUR LEGAL POTENTIAL: IMPACTFUL AND TRANSFORMATIVE PROGRAMS

Explore IE Law School's rigorously designed portfolio of transformative bachelor's, master's, Dual Degree programs and advanced legal programs for professionals meticulously tailored to shape the next generation of influential legal experts.

DISCOVER OUR MASTER'S PROGRAMS

DISCOVER OUR DOUBLE MASTERS IN LAWYERING

Master's Dual Degrees

Bachelor's and Bachelor's dual degrees

EMPOWERING LEGAL PROFESSIONALS FOR SUSTAINABLE IMPACT

Our renowned faculty and practitioners are ready to share in-depth knowledge and expertise, built up over long years of research and practice in leading organizations around the world. Add to this our unique pedagogical style and dynamic, contemporary vision, you will undergo a transformative journey that will shape you into a versatile professional capable of driving impact across any organization.

INTERESTED IN CHATTING WITH STUDENTS OR STAFF?

Our students and staff are always available to share their experiences and help resolve any doubts you might have.

IE INSIGHTS: EXPERT PERSPECTIVES

Insights is IE University’s thought leadership publication for sharing knowledge on management, law, and innovation. We bring fresh ideas from research-based analysis, practitioners, and world-leading experts.

The Dangers of Automation in Administrative Law

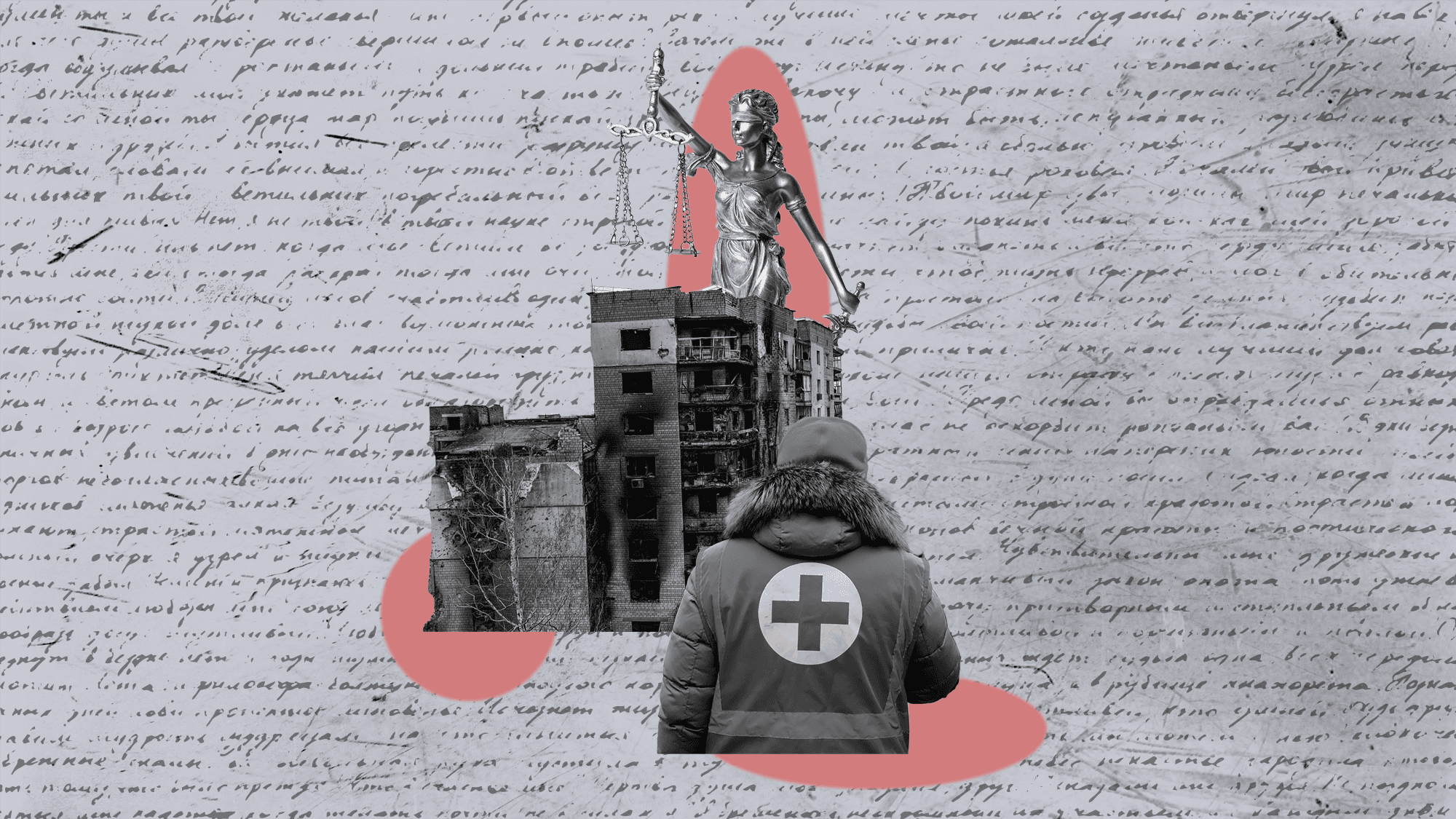

International Humanitarian Law: Navigating Boundaries in Times of Conflict

The Community of Data

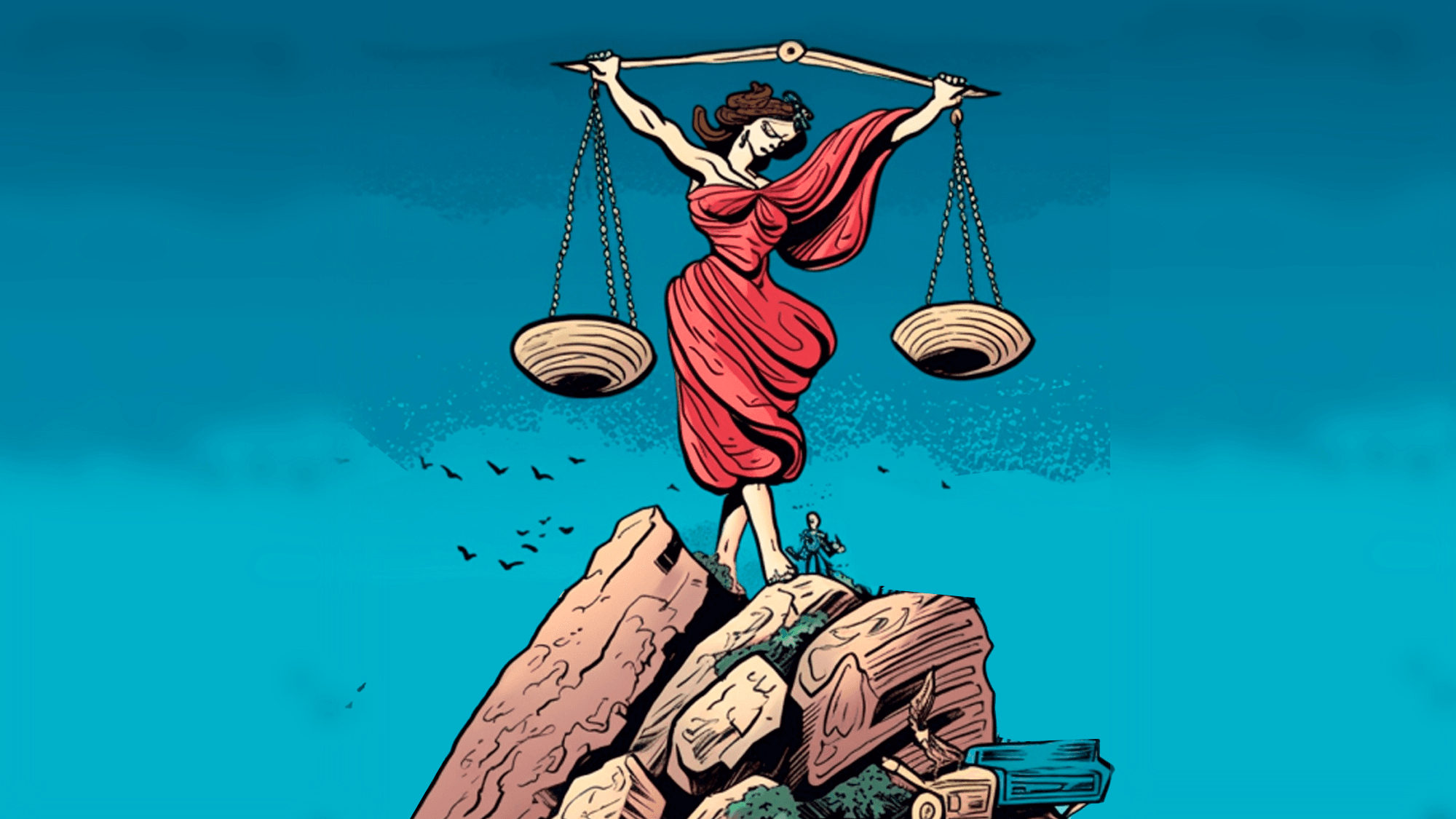

The New Reality of Legal Practice